Gallery

Photos courtesy of Duke University Archives

Segregated seating at Duke University Stadium, Notre Dame versus Duke football game, December 2, 1961 (Duke University Archives). A report prepared in 1962 explained that “the Negro section at the outdoor Stadium is predicated on the assumption that Negroes prefer to sit together and that such separation avoids ‘incidents.’”

First three African American Duke graduates, 1967 (Duke University Archives). Among the “first five” in 1963, Wilhelmina Reuben, Nathaniel White Jr., and Mary Mitchell Harris were the first African American undergraduates to receive their degrees from Duke in 1967.

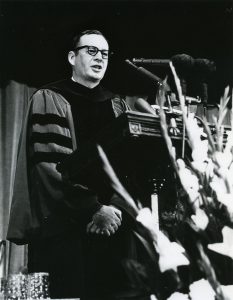

Douglas M. Knight speaking at his inauguration, December 11, 1963 (Duke University Archives). Offered the presidencies of Duke and Cornell at the same time, Knight was, at forty-two, among the youngest university presidents in the nation.

Martin Luther King Jr. speaking to an overflow crowd in Page Auditorium at Duke on November 13, 1964 (Duke University Archives).

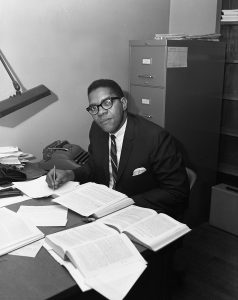

Samuel DuBois Cook, 1966 (Duke University Archives). Political science professor Samuel DuBois Cook became the first African American faculty member at Duke in 1966.

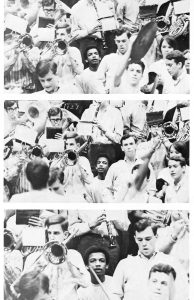

A Black student bandmember remains seated, refusing to participate in the playing of “Dixie” at a Duke athletic event, circa 1968. (photo by Larry Funk; Chanticleer, 1969, p. 34). Among the initial AAS “concerns” presented to the administration, the playing of “Dixie” and display of the Confederate flag at university events, was discontinued in 1968.

Wilhelmina Reuben, May Queen, 1967 (Duke University Archives). In 1967 Wilhelmina Reuben was elected by the Woman’s College as the first Black May Queen in Duke history. Trustee C.B. Houck wrote President Knight that Reuben’s election was in “bad taste” and trustee George M. Ivey Jr. found it “nauseating to contemplate” that Duke would attract students who would make such a choice.

Stokely Carmichael speaks to a full house in Page Auditorium, March 17, 1967 (Duke University Archives). The appearance of the chair of the SNCC at Duke catalyzed Black students to meet as a group for the first time.

Approximately 250 nonacademic employees, students, and other supporters protest outside the Allen Building on April 19, 1967, seeking impartial third-party arbitration of employee grievances (Durham Civil Rights Heritage Project; photo by Bill Boyarsky).

Labor leader Oliver Harvey (center) and an unnamed student distribute Local 77 literature on Duke campus, April 1967 (photo by Bill Boyarsky; Durham Civil Rights Heritage Project).

Black students hold a “study-in” in the anteroom outside President Knight’s office on November 13, 1967, to protest the continued use of off-campus segregated facilities by Duke student organizations (Duke University Archives). Although Knight maintained he was not responding to Black student pressure, the university prohibited the use of segregated facilities by student groups less than four days later.

On April 5, 1968, approximately 250 students, the vast majority of them white, occupy the home of Duke president Douglas Knight following a memorial march for Martin Luther King Jr. (Duke Chronicle, April 8, 1988). Knight gave the students permission to remain overnight and they stayed in the house for thirty-six hours.

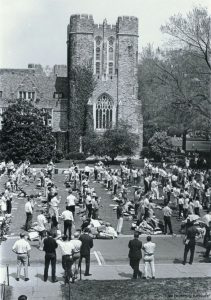

The Silent Vigil, April 1968 (Duke University Archives). The Silent Vigil on the main quadrangle was highly organized. Protesters sat in rows. Rules included “No talking. . . . No eating except at group snack and meal breaks. . . . No sunbathing” and “No singing except at specified periods under the direction of the song leader.”

The Silent Vigil, April 1968 (Duke University Archives). The first protest for most participants, the Silent Vigil had a powerful impact on the individuals involved. One protester said it was “as close as I ever came to a religious feeling.”

The Silent Vigil, April 1968 (Duke University Archives). Silent Vigil participants demanded that Duke’s nonacademic employees be granted the right to bargain collectively. Dining hall workers and students organized picket lines outside the campus dining halls.

The Silent Vigil, April 10, 1968 (Duke University Archives). Silent Vigil protesters remained on the Duke quadrangle even after it started to rain.

The Silent Vigil, April 10, 1968 (Duke University Archives). Left to right: Charles Huestis, Frank Ashmore, Wright Tisdale, student Reed Kramer, and student Jonathan Kinney. The board chair Wright Tisdale and administrators joined in singing “We Shall Overcome” after Tisdale addressed the vigil. “If you saw the picture” of me singing, Tisdale told an alumni group a few months later, “you’d know I wasn’t happy about it.”

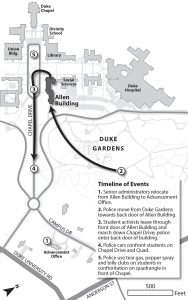

Map of West Campus of Duke University showing movements of administrators, students, and police during the afternoon of the Allen Building takeover on February 13, 1969. Map by Tim Stallman

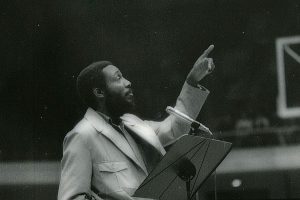

Activist and comedian Dick Gregory speaks to a crowd of 3,000 people at the Duke indoor stadium on February 10, 1969 (Duke University Archives). Knight believed that Gregory’s speech, titled “Nigger,” was “the explosive one” that triggered the Allen Building takeover.

Students inside the Allen Building during the takeover, April 13, 1969 (photo by Lynette Lewis). Left to right: Chuck Hopkins (on phone at desk), C. B. Claiborne (at desk), Bertie Howard (seated on chair), Cheri Riley, unidentified student (seated on desk), Charles Becton, and Clarence Morgan. Students took turns answering the many calls that came in from media, friends, faculty, members of the local Black community, and parents, among others.

The Allen Building takeover, February 13, 1969 (Duke University Archives). The administration immediately adopted a “no negotiations” stance to the protest, and Durham police and state highway patrol were called to campus soon after administrators learned of the takeover. Police in full riot gear assembled in Duke Gardens, awaiting instructions, which came hours later.

The Allen Building takeover, February 13, 1969 (Duke University Archives). A large crowd of white student activists, Black students, sympathetic faculty, and members of the Durham Black community, among others, assembled outside the Allen Building to form a “human shield” to protect the protesters from the police. Once mobilized, police encircled this group.

Police standing outside the Allen Building (Chanticleer, 1969, p.54). One member of the police contingent told a protester years later that having been on standby in Duke Gardens for hours, the officers arrived on the quad “pumped up and primed” and ready to “whip some heads and get this thing in order.”

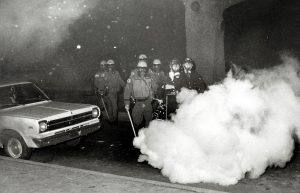

Students on Quad after Allen Building takeover being teargassed, February 13, 1969 (Duke University Archives). Although Black students had left the Allen Building, police determined that it was necessary to clear the quad. “Tear gas was flying everywhere,” one eyewitness said, and “police started hitting people with billy clubs.”

Police approach students on Quad after Allen Building takeover, February 13, 1969 (Duke University Archives). In addition to tear gas, police deployed a pepper gas machine that one observer described as looking like “a combination-vacuum-cleaner-ray-gun.” Police efforts to clear the quad lasted for over an hour.

Policeman approaching unidentified student, February 13, 1969 (Duke University Archives). One student reported seeing police “striking anything in their path.” “Kent State could very well have happened at Duke,” one protester thought later.

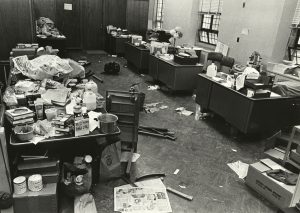

The central records office after the Allen Building takeover, February 13, 1969 (Duke University Archives). Because they exited in haste, students left behind the supplies they had taken into the Allen Building. A sweep of the occupied area showed that no records had been destroyed and little damage had occurred.

“Weapons” brought into the Allen Building (Douglas Knight Records, Duke University Archives). The university presented this picture at the disciplinary hearing as evidence that students had brought “weapons” into the Allen Building. Students maintained that these items were used only to secure the occupied area.